The Ethical Obligation of Accurate and Authentic Racial Photography

Have you seen Google’s Super Bowl commercial promoting Real Tone, its new camera technology that accurately highlights various skin tones?

Real Tone technology, efforts to more authentically photograph Black and brown skin tones, and growing awareness about using color grading to edit photos might make one think we are further away from Shirley card issues than we really are.

Just this week I came across an NFL cornerback Prince Amukamara tweet that made me throw my phone across my living room floor in dismay. In it he appears amidst two white men with inaccurate lighting and overly saturated teeth – virtually invisible except for his mouth being poorly illuminated or saturated due to incorrect exposure issues – under an incorrectly lit environment with inaccurately saturated lips and teeth – “I promise you I’m in this picture…” While some well-meaning Twitter fans responded with edits meant to “fix” exposure issues on their behalf – in truth the problem lies deeper within than that.

Prince Amukamara of Twitter shared Aundre Larrow’s plea, tweeting, “I implore camera, editing and phone companies to improve. Change your metering accordingly; make your flash longer-reaching; soften its trigger…” He’s right – camera companies need to step up.

But before we all rush headlong into technological deficiencies or advances, many of us are so eager to embrace, it is imperative we look back through our lenses at history of photography exerting oppressive control on marginalized communities. Before discussing proper lighting setups for people of Black and brown skin tones or editing skin tones accurately in post processing, take some time doing educational work that does not involve using cameras at all.

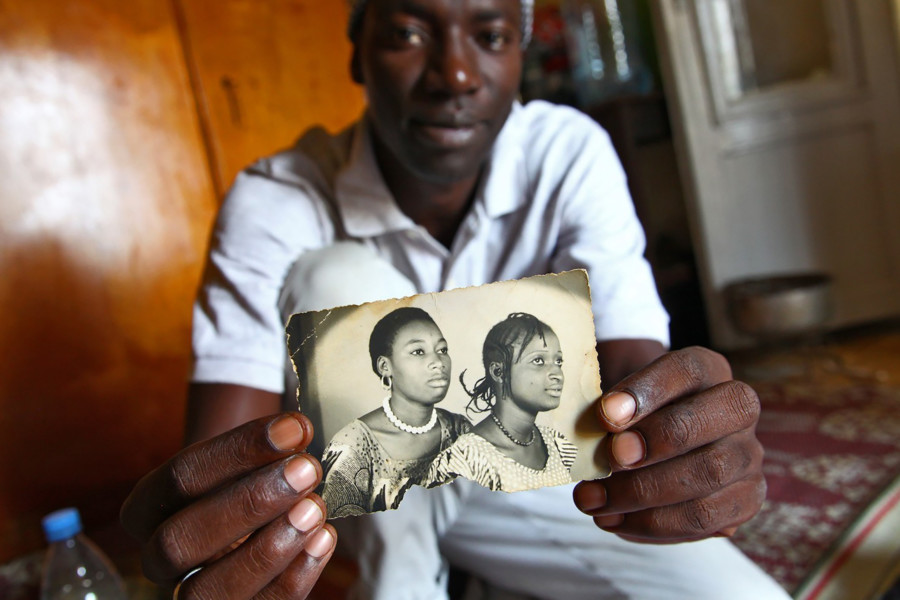

“It is of vital importance to consider the ethics surrounding producing and disseminating photographs. We must acknowledge any harm caused by hierarchies between photographer and sitter or their intersection with racism or sexism, recognize social effects of our photographs, and use photography as an agent of empowerment rather than violence,” writes New York-based documentary photographer Laylah Amatullah Barrayn.

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, an esteemed documentary and portrait photographer based out of New York City who has had work published by Vogue, The New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, BBC and National Geographic is featured here. In addition to photography work she’s given talks at Yale, Harvard, International Center of Photography Tate Modern London Rochester Institute of Technology World Press Photo as well as Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

It’s just one of many insightful essays highlighting the significance of inclusive photographic practices featured in The Photographer’s Guide to Inclusive Photography, our free educational resource developed in conjunction with The Authority Collective.